The Center for Biodiversity and Conservation (CBC) offers a careful definition of the term Biodiversity. The organization states, “Biodiversity (from “biological diversity”) refers to the variety of life on Earth at all its levels, from genes to ecosystems, and can encompass the evolutionary, ecological, and cultural processes that sustain life.”

We will try to unpack this definition as we go.

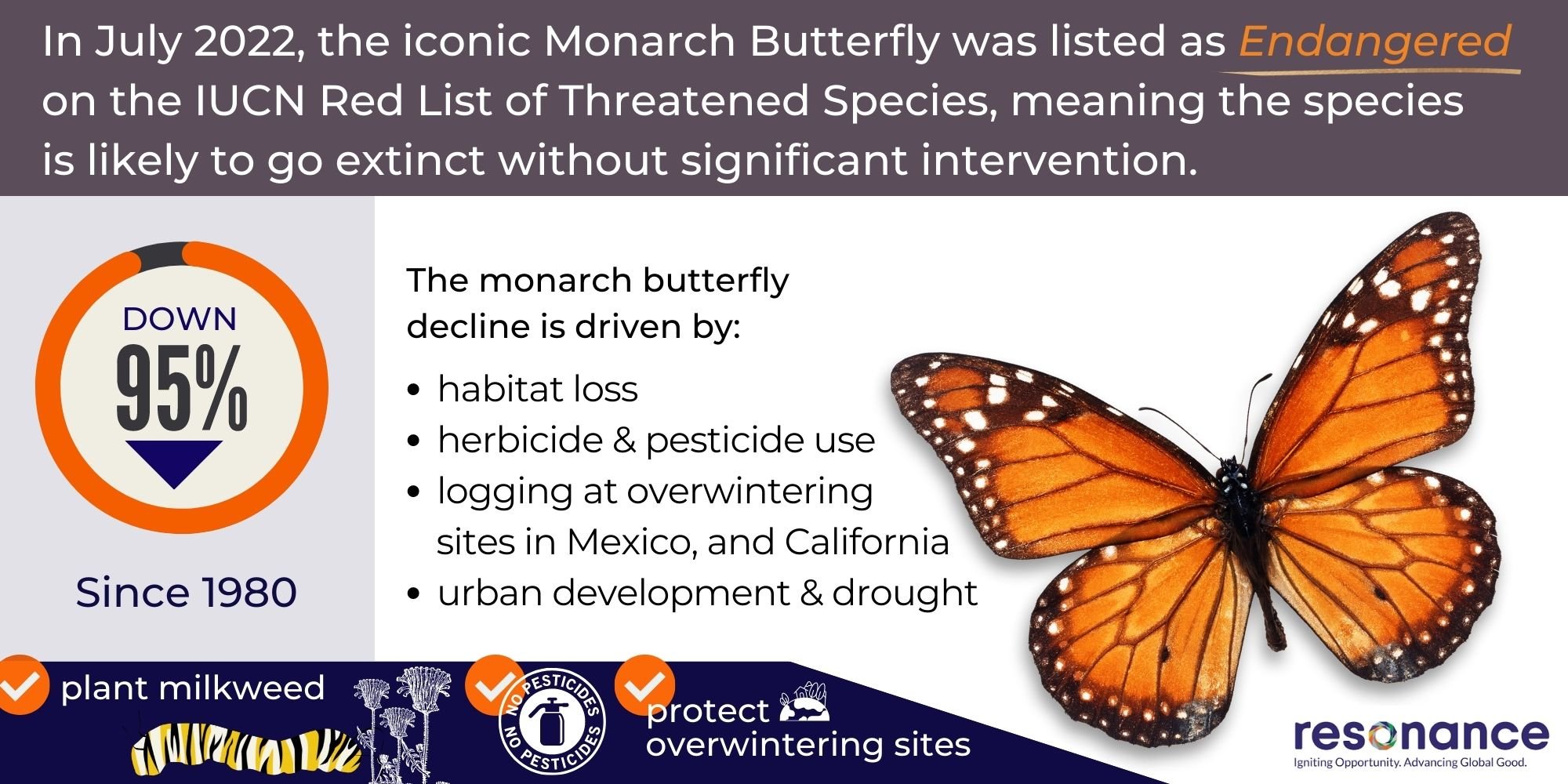

It is important to note that when reported or discussed, ‘Biodiversity’ is often framed through the lens of “loss of” and “threats to,” and for good reason.

In the last 50 years, we have experienced rapid growth of population, human consumption, urbanization, global trade, and expanding supply chains, resulting in humanity using more of the Earth’s resources than it can replenish naturally. And this comes with an astronomical environmental impact price tag.

The Growing Threat Of Biodiversity Loss

Published by the WWF, The Living Planet Report 2020 documents some of these costs in detail, magnifying the sound of the already heightened alarm bells. The report finds that the population sizes of mammals, fish, birds, reptiles, and amphibians have experienced a decline of an average of 68% between 1970 and 2016. Population sizes in the Caribbean and Latin America have experienced the highest decline, at 94%, while globally, freshwater species have been disproportionately impacted, declining 84% of average.

The report finds that the population sizes of mammals, fish, birds, reptiles, and amphibians have experienced a decline of an average of 68% between 1970 and 2016. Population sizes in the Caribbean and Latin America have experienced the highest decline, at 94%, while globally, freshwater species have been disproportionately impacted, declining 84% of average.

Loss of this magnitude is beyond alarming.

We often think of biodiversity and biodiversity loss in terms of what we can see – those rare, threatened, or endangered species we see in media reporting and images in social media. Tigers, pandas, and polar bears are well-known species in the story of biodiversity decline. And despite emotional connection, they don’t always resonate with people to motivate them to action for an array of reasons (that is another forthcoming Resonance Insights article).

Beyond these often-symbolic species in the narrative of threat, biodiversity includes every living thing—from humans to organisms we know little about, such as invertebrates, microbes, and even fungi. What is happening to the life in our soils, or in plant and insect diversity? All of these provide fundamental support for life on Earth and are showing signs of stress.

According to WWF International Director general Marco Lambertini in his opening to the report, it’s even more pronounced.

He notes, “…nature is unravelling, and our planet is flashing red waning signs of vital natural systems failure.”

If we can get beyond the jarring inclusion of the word “failure,” in the task unpacking the initial definition of biodiversity, Lambertini’s inclusion of “systems” here is critically valuable.

Species population trends are important, not only in monitoring individual species health and viability, and given the challenge in measuring biodiversity systemically, species trends can be one indicator of many in the measure of overall ecosystem (systems) health.

There are several threats, often intertwined, contributing to biodiversity loss and ecosystem health discussed in the report that have been well-documented. Here we include the most significant.

What Are The Biggest Threats To Biodiversity?

Sir Robert Watson of the Tyndall Center for Climate Change Research is one of several scientists included in the The Living Planet Report, detailing through his organization’s work the biggest threats to biodiversity.

Land Use Change And Overfishing

The most important direct driver of biodiversity loss in terrestrial systems in the last several decades, he notes, is attributed to land-use change, primarily the conversion of native habitats (forests, grasslands, and mangroves) into agricultural systems, while much of the oceans have been overfished.

Since 1970 these trends have been driven by a doubling of the world’s human population and corresponding growth (fourfold) in the global economy and an increase (tenfold) in world trade.

He explains, “Until 1970, humanity’s Ecological Footprint was smaller than the Earth’s rate of regeneration. To feed and fuel our 21st century lifestyles, we are overusing the Earth’s biocapacity by at least 56%.”

Pollution From Hazardous Wastes, Chemicals And Nutrient Loading

Pollution from hazardous wastes and chemicals is also a significant threat to biodiversity. This includes direct (source) pollutants in the air and water, including oil, plastics, heavy metals and pesticides, for example, as well as indirect sources that are more difficult to measure such as Greenhouse Gasses (CH4, N2O, and CO2).

Nutrient loading, primarily of nitrogen and phosphorous, is also a major and growing cause of biodiversity loss and ecosystem dysfunction.

This enrichment in aquatic and marine environments can result in a chain of undesirable effects, starting with excessive growth of planktonic algae, which increases the amount of organic matter settling to the seabed. Accumulation may be associated with changes in species composition and altered functioning of the food web.

Climate Change

Although the ‘wicked’ problem of global climate change has not been the most important driver of biodiversity loss to date, in the coming decades, it is projected to become as, or more, important than other drivers.

“Climate change adversely affects genetic variability, species richness and populations, and ecosystems. In turn, loss of biodiversity can adversely affect climate – for example, deforestation increases the atmospheric abundance of carbon dioxide, a key greenhouse gas. Therefore, it is essential that the issues of biodiversity loss and climate change are addressed together.”

– Sir Robert Watson

The value of biodiversity and threats of tremendous loss to individual species and regional ecosystems cannot be overstated. Given the realities of climate change and its impacts, maintaining biodiversity and ecosystem health is important to dynamic, global systems as well.

Why Is Biodiversity Important?

Biodiversity is important and fundamental to human life on this planet. We value biodiversity for many reasons, some utilitarian, for what it provides to humans, and some intrinsic, for the value it has in its own right.

According to the data from the United Nations Environment Programme, the value of our ‘natural capital’ – the earth’s stock of renewable and non-renewable resources like soils, plants, minerals, and water, has declined by nearly 40% per person since the 1990s.

Food Security

Despite land-use conversion to agricultural production as a major threat, biodiversity loss threatens food security in the short and long-term.

This is particularly true regarding the vast range of ecosystem functions and services that soil biodiversity provides even beyond food production, including the retention and purification of water, nutrient cycling, soil formation, and the degradation of soil contaminants and regulation of greenhouse gases. Soil biodiversity is critical to sustaining plant, animal, and human health.

Although only an estimated 10% of plant species have been assessed for the global IUCN Red List and current coverage is biased, with trees and threatened species more likely to have been assessed, data from combined assessment techniques have concluded that one in five (22%) plant species are threatened with extinction, concentrated mostly in the tropics.

Not only is plant biodiversity important for medicinal and other ecosystem values globally but sustaining the needs of indigenous communities as well.

Other Utilitarian Provisions

Other utilitarian values of biodiversity include the provision of fiber, water, shelter, energy, medicines, and other genetic materials. In addition, healthy and biodiverse ecosystems provide crucial services such as seed dispersal, pollination, nutrient cycling, water purification, agricultural pest control, flood and storm surge control, and climate regulation.

As noted by the CBC, biodiversity also holds value for potential benefits not yet recognized, such as new medicines and other possible unknown services.

Biocultural Values

If we return to the original definition put forth by the CBC, we note reference to the “cultural processes” – humans and human cultural diversity, as a critical part of biodiversity.

This concept of “biocultural” describes the ways in which biodiversity contributes on non-material levels – inspiration and learning, physical and psychological experiences, and shaping our identities – that are central to quality of life and cultural integrity.

Biodiversity through this biocultural lens describes the dynamic, interconnected, and continually evolving nature of people and place, and the notion that biological and social dimensions of nature and biodiversity are interrelated.

“This symbiotic relationship makes all of biodiversity, including the species, land and seascapes, and the cultural links to the places where we live—be right where we are or in distant lands—important to our wellbeing as they all play a role in maintaining a diverse and healthy planet.”

- The CBC

Why Does Biodiversity Loss Matter?

Sir Robert Watson suggests biodiversity loss is not only an environmental issue but a development, economic, global security, ethical, and moral one.

He believes the continued loss of biodiversity will undermine the achievement of most of the UN Sustainable Development Goals, including poverty alleviation and food, water, and energy security.

Impacts related to biodiversity loss are economic with impacts disproportionately incurred by some countries, communities, and populations more than others.

The threats to biodiversity pose a security issue, insofar as the loss of natural resources, especially in poor developing countries, can lead to conflict. It is an ethical issue because loss of biodiversity hurts the poorest people who depend on it, further exacerbating an already inequitable world; and it is a moral issue because humans have agency in our decisions and actions and should choose not to destroy the living planet.

In this way, biodiversity and preventing loss is a self-preservation issue.

Like other reports before it, The Living Planet Report, as well as an overwhelming body of other scientific literature – sets out a grim diagnosis for our natural world, and consequently for humanity. However, it doesn’t present a rhetoric of hopelessness, but one of necessary and possible change.

Solutions: ‘Bend The Curve’ On Biodiversity Loss

Calls by scientists, environmentalists, and activists to dramatically change how we produce, consume, and protect our interconnected planet for decades are being met today with data-packed modeling capabilities, giving us various proof of concepts and roadmaps to achieve this – to “bend the curve of biodiversity loss.”

A major new International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA)-led study, published in Nature and part of the latest Living Planet Report, was clear in terms of what needs to be done.

"Without ambitious, integrated action combining conservation and restoration efforts with a transformation of the food system, turning the tide of biodiversity by 2050 or earlier will not be possible."

This includes. more specifically:

3 Priority Conservation and Restoration Efforts

- Increasing protected areas to 40% of global terrestrial areas

- Restoration of degraded land (reaching about 8% of terrestrial areas by 2050, and

- Land use planning efforts that balance production and conservation objectives on all managed land.

Without such efforts, the study notes, declines in biodiversity may only be slowed down rather than halted and any potential recovery would remain slow.

Food System Transformation

As bold conservation and restoration efforts alone will likely be insufficient, additional measures are needed to address global pressures on the food system. Efforts to bend the curve of global terrestrial biodiversity include:

- Reducing food waste

- Adapting to diets with a lower environmental impact, and

- Further sustainable intensification and trade.

Integrated action would, however, need to be taken in both areas simultaneously to bend the biodiversity loss curve upward by 2050 or earlier.

How Resonance in Working to Bend the Curve on Biodiversity Loss

Our work at Resonance continues to align with many recommended “bending” approaches and solutions to prevent biodiversity loss.

This includes a track record in promoting sustainable fisheries and mangrove conservation through the Fish Right program, as well as strengthening regional cooperation for sustainable, legal management and trade of fisheries resources in the Asia-Pacific region through the USAID/RDMA Oceans and Fisheries Partnership (USAID Oceans), and pending, funded initiatives in robust partnerships including USAID in other regions.

It also includes an emphasis on regenerative agriculture initiatives and environmental and sustainability approaches to mitigate biodiversity loss and ensure food security and sustainable impact.

These recently-published studies indicate that although we are facing a dire challenge, we may be able to work collaboratively and globally to stabilize and reverse biodiversity loss.

But to have any chance of doing that as early as the scientific community is suggesting, we will need to make transformational changes in the way we produce and consume food as well as engage in bolder, more ambitious conservation efforts, with strategic and collaborative partnerships leading the way.